Do not sever the bonds of the womb.

– Qur’an 4:1

Do not kill your children from fear of poverty.

– Qur’an 17:31

On the Day when the one buried alive will be asked for what sin was she killed.

– Qur’an 81:8–9

Marry and be fruitful, for I will be proud of the multitudes of my community of believers on the Day of Judgment.

– Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ

To die by other hands more merciless than mine.In English, the term we define ourselves with, human being, emphasizes “being” over doing. It is not our actions that mark us as humans but our mere being. When, then, do we come to be? When does that being we identify as human first become human? The answer is consequential for many reasons, not the least of which is that our nation’s foundational document states that all human beings are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights” that include the rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The question of when human life begins stubbornly remains a central point of contention in the debate, now raging for half a century, regarding the ethics of abortion. The Supreme Court made its decision, but for many, it is far from a settled matter.

No; I who gave them life will give them death.

Oh, now no cowardice, no thought how young they are,

How dear they are, how when they first were born;

Not that; I will forget they are my sons

One moment, one short moment—then forever sorrow.

– Euripides’ Medea

Beyond our borders, meanwhile, induced abortion rates are increasing in developing nations, despite declining slightly in developed nations; an estimated one-quarter of all pregnancies worldwide end in abortion.1 The debate over abortion still rages across parts of Europe and remains contentious in North Africa, the Middle East, Asia, as well as Central and South America. While the Catholic Church continues to prioritize abortion as an egregious social ill, for many, abortion has become an acceptable option for dealing with unwanted pregnancies. Increasingly, some Muslims are adding their voices to the conversation—some even supporting legalization in areas where abortion remains illegal.

Given this global trend, it becomes all the more urgent to re-examine the normative view of infanticide and abortion in the Islamic legal tradition, which relies on the Qur’an, prophetic tradition, and scholastic authority for its proofs.

Abortion derives from the Latin word aboriri,2 meaning “to perish, disappear, miscarry.”3 The verb to abort is both intransitive (meaning to “miscarry” or “suffer an abortion”) and transitive (“to effect the abortion of a fetus”).4 In standard English, we also use the word to connote the failure of something, as “an aborted mission”—something that ends fruitlessly. As a noun, abortion means “the expulsion of a fetus (naturally or esp. by medical induction) from the womb before it is able to survive independently, esp. in the first 28 weeks of a human pregnancy.”5

Historically, civilizations and religious traditions often grouped abortion with infanticide—defined as “the killing of an infant soon after birth” by the Oxford Modern English Dictionary. Indeed, even some modern philosophers link abortion and infanticide by arguing for what they euphemistically term “after-birth abortions.”6 Reviewing the sordid history of infanticide since the Axial Age7 and how the different faith traditions inspired a change in attitudes about both practices helps sets the stage for understanding the Islamic ethical vision toward abortion, which depends ultimately, as we’ll see, on the central question of when human life begins. The Mālikī legal school—or the Way of Medina,8 as it was known—offers modern Muslims a definitive response rooted in the soundest Islamic methodology to a seemingly intractable problem vexing our world today.

The references to induced abortion in early Islam are scarce and

generally occur in books of jurisprudence, in sections on blood

compensation (diyah), which examine situations where someone

caused a woman to lose her child. The permissibility of abortion was

inconceivable to early Muslims even though abortifacients were readily

available.

The Persian polymath Avicenna83 (d. 428/1037) records more than forty abortifacients in his magisterial medical compendium al-Shifā’. In the only section dealing with abortion entitled “On Situations Requiring an Abortion,” he writes: “There may be a situation in which you need to abort a fetus from the uterus in order to save the mother’s life.”84 He lists three conditions where a pregnancy threatens a woman’s life and then lists several ways to induce an abortion in cases where those conditions exist. He gives no other reasons for aborting a fetus.85

The sole exception among Mālikī scholars regarding abortions was Imam al-Lakhmī86 (d. 478/1085), who permitted abortion of an “embryo” (nuţfah) before forty days. Arguably, he would recant his position if he knew what we know today about fetal development. Nevertheless, his position was never taken up for serious discussion by any Mālikī scholar and remains a mere mention as a sole dissenting voice in books of legal responsa.

Far too often today, the positions favoring the permissibility of abortions in other schools of jurisprudence are presented in articles and fatwas, without the nuance that one finds in the original texts. This results from either disingenuousness or shoddy scholarship. For instance, Imam al-Ramlī87 (d. 1004/1596), held in high esteem in the Shāfi¢ī school, is invariably quoted as permitting abortion, but he clearly qualifies his position. He states, for instance, “If the embryo results from fornication, [abortion’s] permissibility could be conceivable (yutakhayyal) before ensoulment.”88 He also believed that the stages of nuţfah, ¢alaqah, and muđghah, occurred during the first 120 days, but we now know they occur in the first 40 days; the question remains whether he would alter his position had he known this. Mistakenly, he also claims that Imam al-Ghazālī, perhaps the most important legal philosopher in the history of Islam, did not categorically prohibit abortion. In The Revival of Religious Sciences, Imam al-Ghazālī89 discusses various positions of scholars on birth control and then states,

Clearly in this passage, Imam al-Ghazālī prohibits abortion, in no uncertain terms, during each stage of fetal development but opined that as the fetus developed within the womb, the severity of the crime increased by degrees.

Even regarding coitus interruptus, according to a sound tradition from Śaĥīĥ Muslim, the Prophet ﷺ stated, “That is a hidden type of infanticide (al-wa’d al-khafiyy).”91 Scholars interpret that to mean it is disliked, but the Prophet’s strong language concerning birth control by likening it to a hidden form of infanticide indicates that aborting a fetus would surely be considered infanticide. And this is the position of the jurist Imam Ibn Taymiyyah92 (d. 728 AH/1328 CE), who asserts that abortion is prohibited by consensus: “To abort a pregnancy is prohibited (ĥarām) by consensus (ijmā¢) of all the Muslims. It is a type of infanticide about which God said, ‘And when the buried alive is asked for what sin was she killed,’ and God says, ‘Do not kill your children out of fear of poverty.’”93

The Persian polymath Avicenna83 (d. 428/1037) records more than forty abortifacients in his magisterial medical compendium al-Shifā’. In the only section dealing with abortion entitled “On Situations Requiring an Abortion,” he writes: “There may be a situation in which you need to abort a fetus from the uterus in order to save the mother’s life.”84 He lists three conditions where a pregnancy threatens a woman’s life and then lists several ways to induce an abortion in cases where those conditions exist. He gives no other reasons for aborting a fetus.85

The sole exception among Mālikī scholars regarding abortions was Imam al-Lakhmī86 (d. 478/1085), who permitted abortion of an “embryo” (nuţfah) before forty days. Arguably, he would recant his position if he knew what we know today about fetal development. Nevertheless, his position was never taken up for serious discussion by any Mālikī scholar and remains a mere mention as a sole dissenting voice in books of legal responsa.

Far too often today, the positions favoring the permissibility of abortions in other schools of jurisprudence are presented in articles and fatwas, without the nuance that one finds in the original texts. This results from either disingenuousness or shoddy scholarship. For instance, Imam al-Ramlī87 (d. 1004/1596), held in high esteem in the Shāfi¢ī school, is invariably quoted as permitting abortion, but he clearly qualifies his position. He states, for instance, “If the embryo results from fornication, [abortion’s] permissibility could be conceivable (yutakhayyal) before ensoulment.”88 He also believed that the stages of nuţfah, ¢alaqah, and muđghah, occurred during the first 120 days, but we now know they occur in the first 40 days; the question remains whether he would alter his position had he known this. Mistakenly, he also claims that Imam al-Ghazālī, perhaps the most important legal philosopher in the history of Islam, did not categorically prohibit abortion. In The Revival of Religious Sciences, Imam al-Ghazālī89 discusses various positions of scholars on birth control and then states,

It should not be viewed like abortion or infanticide, because that involves a crime against something that already exists, although the creative process has degrees: the first degree of existence is the male sperm reaching the female egg in preparation for the beginning of life. To disrupt that is criminal (jināyah). If it becomes a clot or a lump, the crime is even more heinous. And should ensoulment occur and the form completed, the crime is even more enormous; the most extreme crime, however, is to kill it once it has come out alive.90

Clearly in this passage, Imam al-Ghazālī prohibits abortion, in no uncertain terms, during each stage of fetal development but opined that as the fetus developed within the womb, the severity of the crime increased by degrees.

Even regarding coitus interruptus, according to a sound tradition from Śaĥīĥ Muslim, the Prophet ﷺ stated, “That is a hidden type of infanticide (al-wa’d al-khafiyy).”91 Scholars interpret that to mean it is disliked, but the Prophet’s strong language concerning birth control by likening it to a hidden form of infanticide indicates that aborting a fetus would surely be considered infanticide. And this is the position of the jurist Imam Ibn Taymiyyah92 (d. 728 AH/1328 CE), who asserts that abortion is prohibited by consensus: “To abort a pregnancy is prohibited (ĥarām) by consensus (ijmā¢) of all the Muslims. It is a type of infanticide about which God said, ‘And when the buried alive is asked for what sin was she killed,’ and God says, ‘Do not kill your children out of fear of poverty.’”93

The overwhelming majority of Muslim scholars have prohibited

abortion unless the mother’s life is at stake, in which case they all

permitted it if the danger was imminent with some difference of opinion

if the threat to the mother’s life was only probable. A handful of later

scholars permitted abortion without that condition; however, each

voiced severe reservations. Moreover, none of them achieved the level of

independent jurist (mujtahid). To present their opinions on

this subject as representative of the normative Islamic ruling on

abortion is a clear misrepresentation of the tradition. Those scholars

permitted abortion only prior to ensoulment, which they thought occurred

either within 40 days or 120 days. Further, these opinions were based

on misinformation about embryology and a failure to understand the

nuances of the Qur’anic verses and hadiths relating to embryogenesis.

Modern genetics shows that the blueprint for the entire human being is

fully present at inception, and thus we must conclude once the

spermatozoon penetrates the ovum, the miracle of life clearly begins.

Ensoulment occurs after the physical or animal life has begun. Given

that twenty percent of fertilized eggs spontaneously abort in the first

six weeks after inception, the immaterial aspect of the human being,

referred to as “ensoulment” (nafkh al-rūĥ), would logically occur after that precarious period for the fertilized egg at around forty-two days; but God knows best.

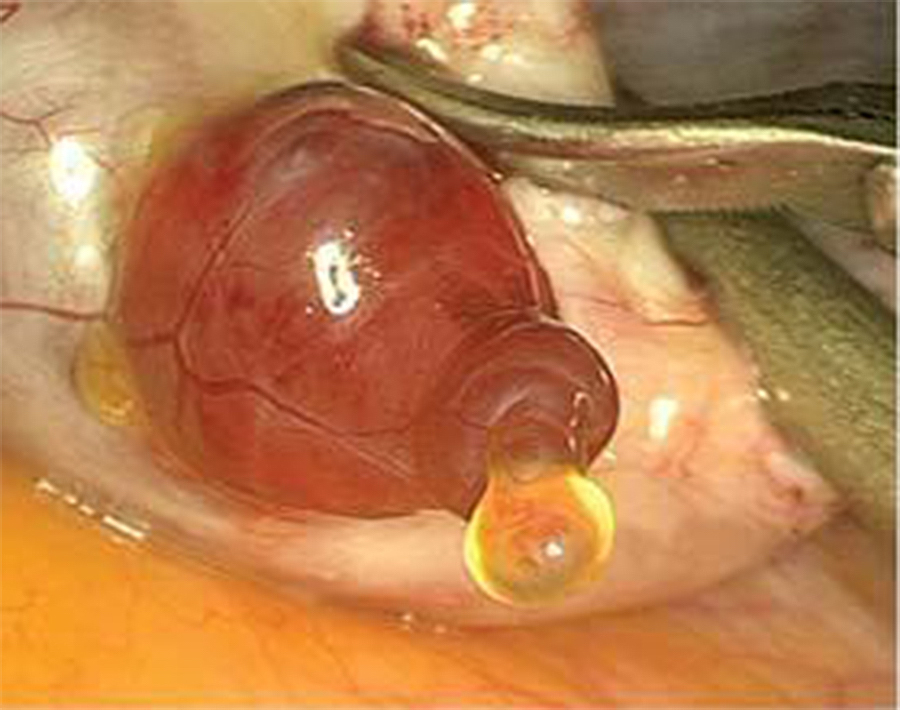

Abortions, especially those performed after forty days of fetal development, also violate a different teaching of the Islamic tradition: the prohibition of mutilation. A six-week-old fetus clearly has the form of a child, with budding arms and legs, a head, the beginning of eyes and ears. Imagery of actual abortions performed is pervasive in its depictions of ripped arms and legs from the bodies of fetuses. Ibn ¢Abd al-Barr94 (d. 463/1071) said, “There is no disagreement on the prohibition of mutilation.”95

The Qur’an states that God created us in stages (71:14). Each of these stages—the zygote, the embryo, the clot of cells, the lump formed and unformed, and finally the growing fetus—is a stage every human being experiences. The Prophet ﷺ said, “God says, ‘I derived the womb (raĥim) from My own Name, the Merciful (al-Raĥmān), so whoever severs the womb bond, I will sever him from My mercy.’”96 What constitutes a greater severance of the womb bond than aborting a fetus bonded to the womb? The act of abortion surely “severs the womb bond,” and the womb is a place the Qur’an calls “a protected space” (23:13), meaning God is its protector. Any act of aggression on that sacred space aggresses on a place made sacred by the Creator of life itself.

The Arabic word for “womb” (raĥim) has an etymological relation to the word for “sanctity” (ĥurmah) in what Arabic linguists call “the greater derivation.” The womb has a divine sanctity. God created it as the sacred space where the greatest creative act of the divine occurs: the creation of a sentient and sapiential being with the potential to know the divine. The miraculous inevitability of a fertilized egg occurs only by the providential care of its Creator. Each forebear—from the two parents to their four grandparents to their eight, exponentially back to a point where they eventually invert back to only two people—had to survive wars, famines, childhood sicknesses, natural disasters, accidents, and every other obstacle to the miracle that stands as the myriad number of people alive today. We are each a part of an unbroken chain back to the first parents.

Extreme poverty and the desire for independence from children in a world that has devalued motherhood through intense individualistic social pressures related to meritocracy, psychology, and even the misuse of praiseworthy gender egalitarianism are the primary reasons people in the West today choose abortions. No doubt, many women are genuinely challenged and feel inadequate and unprepared as mothers. The largest demographic among the poor in America remains single mothers. Abortions motivated by knowing, through the miracle of ultrasound technology, that the offspring will be female, as is the case in China and India, can be seen as an “advanced” form of the infanticide that was practiced in ancient times after birth. Arguably, if the pre-Islamic Arabs had possessed ultrasound and modern methods of abortion, they would not have waited for the female child to come to term; rather, they would have aborted the infant in the early stages of pregnancy. Genetic testing can also now predict (not always reliably) any number of serious disabilities a child may be born with. Absent any religious injunctions on the sanctity of life, abortion is arguably a “valid” way of dealing with unwanted pregnancies and overpopulation, not to mention the promotion of eugenics.

When the angels inquired as to why God would place in the earth “those who shed blood and sow corruption,” God replied, “I know what you do not” (Qur’an 2:30). God knew there would be righteous people who would refuse to shed blood. Abortions are noted for the blood that flows during and after them. For anyone who believes in a merciful Creator who created the human being with purpose and providence, abortion, with rare exception, must be seen for what it is: an assault on a sanctified life, in a sacred space, by a profane hand.

https://renovatio.zaytuna.edu/article/when-does-a-human-fetus-become-human

Abortions, especially those performed after forty days of fetal development, also violate a different teaching of the Islamic tradition: the prohibition of mutilation. A six-week-old fetus clearly has the form of a child, with budding arms and legs, a head, the beginning of eyes and ears. Imagery of actual abortions performed is pervasive in its depictions of ripped arms and legs from the bodies of fetuses. Ibn ¢Abd al-Barr94 (d. 463/1071) said, “There is no disagreement on the prohibition of mutilation.”95

The Qur’an states that God created us in stages (71:14). Each of these stages—the zygote, the embryo, the clot of cells, the lump formed and unformed, and finally the growing fetus—is a stage every human being experiences. The Prophet ﷺ said, “God says, ‘I derived the womb (raĥim) from My own Name, the Merciful (al-Raĥmān), so whoever severs the womb bond, I will sever him from My mercy.’”96 What constitutes a greater severance of the womb bond than aborting a fetus bonded to the womb? The act of abortion surely “severs the womb bond,” and the womb is a place the Qur’an calls “a protected space” (23:13), meaning God is its protector. Any act of aggression on that sacred space aggresses on a place made sacred by the Creator of life itself.

The Arabic word for “womb” (raĥim) has an etymological relation to the word for “sanctity” (ĥurmah) in what Arabic linguists call “the greater derivation.” The womb has a divine sanctity. God created it as the sacred space where the greatest creative act of the divine occurs: the creation of a sentient and sapiential being with the potential to know the divine. The miraculous inevitability of a fertilized egg occurs only by the providential care of its Creator. Each forebear—from the two parents to their four grandparents to their eight, exponentially back to a point where they eventually invert back to only two people—had to survive wars, famines, childhood sicknesses, natural disasters, accidents, and every other obstacle to the miracle that stands as the myriad number of people alive today. We are each a part of an unbroken chain back to the first parents.

Extreme poverty and the desire for independence from children in a world that has devalued motherhood through intense individualistic social pressures related to meritocracy, psychology, and even the misuse of praiseworthy gender egalitarianism are the primary reasons people in the West today choose abortions. No doubt, many women are genuinely challenged and feel inadequate and unprepared as mothers. The largest demographic among the poor in America remains single mothers. Abortions motivated by knowing, through the miracle of ultrasound technology, that the offspring will be female, as is the case in China and India, can be seen as an “advanced” form of the infanticide that was practiced in ancient times after birth. Arguably, if the pre-Islamic Arabs had possessed ultrasound and modern methods of abortion, they would not have waited for the female child to come to term; rather, they would have aborted the infant in the early stages of pregnancy. Genetic testing can also now predict (not always reliably) any number of serious disabilities a child may be born with. Absent any religious injunctions on the sanctity of life, abortion is arguably a “valid” way of dealing with unwanted pregnancies and overpopulation, not to mention the promotion of eugenics.

When the angels inquired as to why God would place in the earth “those who shed blood and sow corruption,” God replied, “I know what you do not” (Qur’an 2:30). God knew there would be righteous people who would refuse to shed blood. Abortions are noted for the blood that flows during and after them. For anyone who believes in a merciful Creator who created the human being with purpose and providence, abortion, with rare exception, must be seen for what it is: an assault on a sanctified life, in a sacred space, by a profane hand.

https://renovatio.zaytuna.edu/article/when-does-a-human-fetus-become-human

No comments:

Post a Comment